|

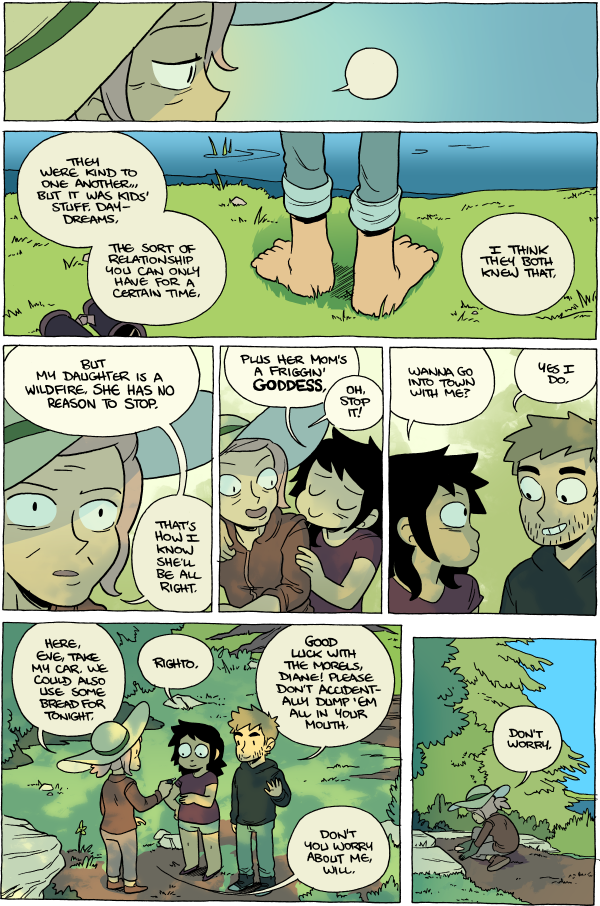

This is a sort of boundary I found hard to accept in early adulthood: the parent who won’t burden the children with their problems, no matter how serious. But what experience do the characters of OP have caring for anyone but themselves? Gradually they’re taking on the needs of friends, romantic and professional partnerships. But being capital-d Depended on is either a brand new or perfectly foreign concept. They’re circling around what someone like Diane actually wants and needs from them. |

"Good luck with the morels, Diane!" No pun intended!

Man, in my mid thirties and as a parent now to a near 5 year old, what I want and need from my peers and younger adults in my life looks something like:

-Love and acceptance for who I am, faults included

-Maybe around to lend a hand when I need one to meet all my commitments and keep the house from descending into total chaos

I do need stability in my life, and as someone who has always struggled to make close friends, I think there is an element of needing to know someone is there, if not daily, then multiple times a week. Not necessarily in person, but just a text to know they're thinking of me. Then again, my best friends have gone their own ways for years only to circle back around and re-establish conversation like we never stopped.

As we get older, we just need to know people are there, and will be there.

That last panel seems kind of ominous for some reason.

I find this kind of take a little baffling. Maybe Marek would, too?

Or maybe it pairs with the chill lack of judgment that almost all the characters had throughout this comic, and which I never possessed in temperament or upbringing. It's always amazed me that Hanna didn't tear into Puget Sean for constantly having his hands all over Marigold when she didn't like it. That was shit I was learning to do at 17.

My teens and college years were full of caring for people, as were my those of my friends. Friends with angry or abusive parents, guy friends who were inappropriately handsy with girls in our group, friends who were depressed or suicidal, friends who were about to be de-registered from classes because they didn't have tuition money.

When I think of the religious community I was raised in, I think all the fretting it pushed me to do for all the people in my life who were Going To Hell and getting me to do street evangelism? That shit was terrible.

But the part where I had a moral responsibility to step in and speak up? To look for people with problems and see what I could do to help? To think about putting others first?

All of that was really good preparation for being a good friend and being able to cope with other people's problems. It took awhile to develop the skills to do it well, but the concept wasn't new even when I was in college.

It's a great question: what does an adult need from their community, from younger people?

I guess what I hope to impart to my own kid as soon as possible is to be *present* with someone who is suffering:

~don't try to discount it

~don't try to explain it away

~don't try to find the bright side

~don't tell them how it will turn out fine or it's for the best

~don't try to change the subject

~don't get weirded out

~don't try to figure out a perfect wise answer

~don't say you know exactly how they feel or that you've been through the same thing

The therap-ese for it is "holding space". Like all therap-ese it sounds a little cheesy. But the best thing I learned from friends in college, in both giving and receiving comfort, is to drop all those distancing maneuvers. Allow that person's pain to be present and alive between you. Don't try to hide it, or obscure it, or hide yourself. See it, see them, be fully there.

It takes practice, not letting the fear that comes with another person's pain dictate your response.

And it works as well with a little kid who's been made fun of at school as a despairing teen or an adult who's just been diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor.